Large-Scale Neural Consolidation in BMI Learning

Introduction

Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) are a class of neuroprosthetic devices that uses signals recorded directly from the brain and translates them into actions taken by an effector such as a cursor or robotic arm. Many past studies have shown adaptation in neurons used in controlling the BMI, but it is unclear how the other neurons in the brain adapt.

Methods

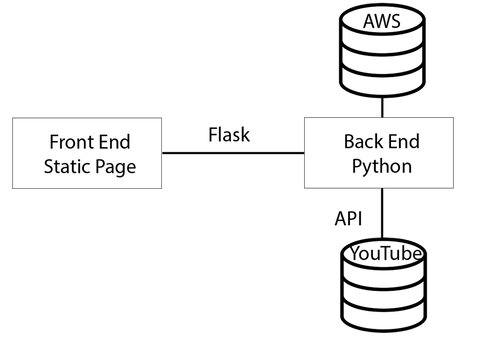

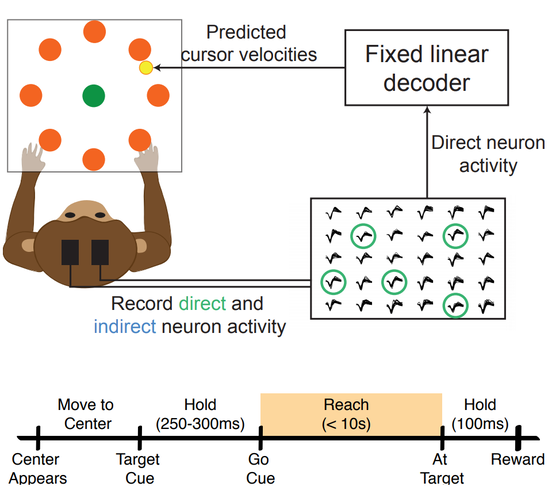

Rhesus macaques were trained to move a computer cursor using a BMI. Each trial consisted of going from a center target to one of eight peripheral targets (Figure 1). Neurons from motor regions of the cortex were recorded and decoded using a linear Weiner filter. To see how neurons directly controlling the BMI (direct neurons) adapted differently than other neurons, we also recorded additional cells that were not used for decoding (indirect neurons).

Figure 1. Rhesus macaques controlled a BMI in 2D space, moving a cursor (yellow) from a center target (green) to one of eight peripheral targets (orange) per trial. Neurons were recorded from motor cortex but only a subset (green) were used for decoding using a Weiner filter. Animals were instructed to hold at the start and terminus of each trial before receiving a reward.

Results

We first asked if the reorganization found in direct cells was common to indirect neurons as well. Neurons in motor regions tend to have what we call preferred tuning directions, meaning that neurons tend to have increased activity when movements of the arm (or computer cursor in this case) go in certain directions. Note that each neuron has its own preferred tuning direction. Consistent with past results, we find that direct neurons change their tuning directions drastically in early learning, but those changes stabilize in later learning (Figure 2). Interestingly, we find a similar change in indirect neurons where preferred tuning directions change in early learning, then stabilize in late learning.

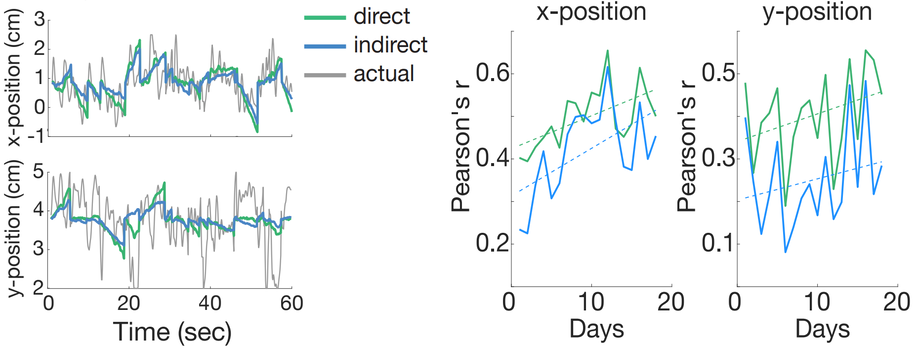

The changes we saw in tuning directions of indirect neurons implied that indirect neurons may adapt in similar ways to direct neurons. Thus, we asked how well we could decode kinematic activity from indirect neural activity. To answer this, we used a simple linear model to regress indirect activity (15 neurons) onto the x and y positions of the computer cursor over time. As hypothesized, we found that the indirect activity was able to predict cursor movements nearly as well as the direct neurons even though the indirect neurons did not inherently drive the BMI (Figure 3). Furthermore, these modeling predictions became better over learning for both subpopulations indicating a consolidation of neural activity over time, leading to more stereotyped control.

To examine this consolidation, we used factor analysis (FA) to determine how much of the neural variance was captured in correlated spaces compared to uncorrelated, private spaces. Unlike principal component analysis, FA does not force the axes to be orthogonal, making it a more lax model for finding low-dimensional structures in data (which we refer to as subspaces). Figure 4A shows a conceptual diagram of how we use the FA model to decompose neural variance into correlated (shared) spaces and independent (private) spaces. From the model, we estimate the amount of activity that's consolidated by calculating the proportion of total variance captured in shared spaces. That is,

\[SOT = \frac{\Sigma^{shared} }{ \Sigma^{total}} \]

We found that the combined population of neural activity became consolidated over learning, and that consolidation wasn't driven by a particular subpopulation. Rather, both direct and indirect neurons collapsed onto low-dimensional subspaces as control of the BMI improved (Figure 4B).

Discussion

Overall, we find that both direct and indirect subpopulations of neurons adapt in similar ways as BMI control improves. Furthermore, they adapt in concert, consolidating onto lower dimensional subspaces together over time, indicating a large-network approach to neuroprosthetic learning. These results are exciting as they suggest that neuroplasticity driven by BMIs is not unique to neurons used for decoding, but may exist in other regions of the brain, making BMIs a potentially efficient solution for inducing neuroplasticity in large cortical areas.